Imperative languages organize programs in procedures and subroutines.

A programming paradigm where instructions are given to the computer in a step-by-step manner, detailing how to achieve a desired result by explicitly changing the program's state.

Fizzbuzz, in BASIC.

2 LET I:I+1, F:I%3=0, B:I%5=0 3 IF F PRINT "FIZZ"; 4 IF B PRINT "BUZZ"; 5 IF F+B=0 PRINT I; 6 PRINT "" 7 IF I<101 GOTO 2 8 END

Fizzbuzz, in C.

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

for (int i = 1; i <= 100; i++) {

if (i % 15 == 0)

printf("FizzBuzz\n");

else if (i % 3 == 0)

printf("Fizz\n");

else if (i % 5 == 0)

printf("Buzz\n");

else

printf("%d\n", i);

}

return 0;

}

Fizzbuzz, in Pascal.

program FizzBuzz;

var

i : integer;

begin

for i := 1 to 100 do

if i mod 15 = 0 then

writeln('FizzBuzz')

else if i mod 3 = 0 then

writeln('Fizz')

else if i mod 5 = 0 then

writeln('Buzz')

else

writeln(i)

end.

Fizzbuzz, in Smalltalk-80.

| i fizz buzz | i _ 1. 100 timesRepeat: [ fizz _ i\\3=0. buzz _ i\\5=0. (fizz) ifTrue: [Transcript show: 'Fizz']. (buzz) ifTrue: [Transcript show: 'Buzz']. (fizz | buzz) ifFalse: [Transcript show: i printString]. Transcript cr. i _ i + 1. ]

Fizzbuzz, in Hypercard.

on mouseUp put 1 into n put 1 into fizz put 1 into buzz repeat 100 if fizz is 3 and buzz is 5 then put "FizzBuzz" into line n of background field "Output" put 0 into fizz put 0 into buzz else if fizz is 3 then put "Fizz" into line n of background field "Output" put 0 into fizz else if fizz is 5 then put "Buzz" into line n of background field "Output" put 0 into buzz else put n into line n of background field "Output" end if put n+1 into n put fizz+1 into fizz put buzz+1 into buzz end repeat end mouseUp

10 PRINT "Hello World"

This guide is written specifically for the Sunflower BASIC implementation, but it should still give a general idea of how to use the language's primitives which are also found in most BASIC implementations.

Introduction

A BASIC program is made of lines beginning with a line number, followed by an operand and an expression. Evaluation walks through the lines of the program in order from small to large until the program reaches the END keyword.

1 REM This is a comment. 2 LET I:I+1, F:I%3=0, B:I%5=0 3 IF F PRINT "FIZZ"; 4 IF B PRINT "BUZZ"; 5 IF F+B=0 PRINT I; 6 PRINT "" 7 IF I<100 GOTO 2 8 END

Expressions can include numbers, variables and arithmetic operators. Numbers are decimal, but can be prefixed with $ for hexadecimal, there are no precedence rules.

10 LET A:6+7 20 PRINT 52+$20*A 30 END

1092

Valid arithmetic operators inside of expressions are as follow:

- + sum

- - difference

- * product

- / quotient

- % remainder

- & and

- | or

- < less than

- > greater than

- = equal

- ! unequal

Interpreter

The interpreter below allows you to play with the examples on this page.

Variables

Variables are single uppercase letters of the alphabet that can store the value of a number. The value of a variable is set with the LET command.

10 LET A:123 20 PRINT "The value of A is " A "." 30 END

The value of A is 123

The R variable is special, reading its value will always give a random number between 0 and 65536. For example, if you wanted to do a program to roll a 6-sided dice:

10 PRINT "You rolled " R%6+1 "." 30 END

You rolled 5.

When a variable is followed by a dot and an expression, the variable to read or write will have an offset equal to the value of the expression:

10 LET X:2, A.X:808 20 PRINT C 30 END

808

Loops

Loops are created by jumping back to the start of the loop with a GOTO, until a specific condition is met with IF. Using a variable as counter, a program can loop over a number of lines five times:

10 LET I:0 20 PRINT "Count: " I 25 LET I:I+1 30 IF I<5 GOTO 20 40 END

Count: 0 Count: 1 Count: 2 Count: 3 Count: 4

Loops can also be nested using two counters:

10 LET A:0 20 LET B:0 21 PRINT A ", " B 22 LET B:B+1 23 IF B<3 GOTO 21 30 LET A:A+1 31 IF A<3 GOTO 20 32 END

Functions

Functions are created with GOSUB, similarly to GOTO, this operation moves evaluation to a different line, except that they keep a return address in memory to be jumped back to upon RETURN.

1 LET N:5 2 GOSUB 50 3 END 49 REM Fib(N) 50 LET A:3, B:1 51 LET C:A, A:3*A-B, B:C, I:I+1 52 IF I<N GOTO 51 53 PRINT "Result: " C 54 RETURN

Result: 144

Interaction

The INPUT statement, will halt the execution and wait for an input. This can be used to store a value into a variable. Arrows and buttons will instantly send a value:

1 CLS 2 PRINT "Press a button, an arrow or input a number:" 3 INPUT X 4 IF X=0 GOTO 8 5 PRINT "Value: " X 6 GOTO 3 7 END 8 PRINT "Good bye." 9 END

Manual

| Hypervisor | RUN | Used to begin program execution at the lowest line number. |

|---|---|---|

RUN | ||

LIST | Causes part or all of the user program to be listed. If no parameters are given, the whole program is listed. A single expression parameter in evaluated to a line number which, if it exists, is listed. A two expressions will print a range of lines. | |

LIST 200 LIST 10,30 LIST | ||

CLEAR | Formats the user program space, deleting any previous programs. If included in a program the program becomes suicidal when the statement is executed. | |

CLEAR | ||

| Core | REM | Permits to add remarks to a program source. |

REM This is a comment. | ||

LET | Assigns the value of an expression to a variable. | |

LET A:123/2, B:$20%2 | ||

IF | If the result of the expression is not zero, the statement is executed; if False, the associated statement is skipped. | |

IF A>B-2 PRINT "A is greater." | ||

GOTO | Changes the sequence of program execution. | |

GOTO 50+A>B | ||

END | Must be the last executable statement in a program. Failure to include an END statement will result in an error stop after the last line of the program is executed. | |

END | ||

| Subroutines | GOSUB | Changes the sequence of program execution, and remembers the line number of the GOSUB statement, so that the next occurrence of a RETURN statement will result in execution proceeding from the statement following the GOSUB. |

GOSUB 220 | ||

RETURN | Transfers execution control to the line following the most recent unRETURNed GOSUB. If there is no matching GOSUB an error stop occurs. | |

RETURN | ||

| I/O | PRINT | Prints the values of the expressions and/or the contents of the strings in the console. To print the result of an expression as an ascii character, use #$41, to print the character A, end with a semi-colon to print without a linebreak. |

PRINT "The result is: " A+B | ||

INPUT | Halts evaluation, and assigns the result of expressions to each of the variables listed in the argument. Expressions are entered sequencially and separated by a line break, a list of two arguments, will expect two input lines. | |

INPUT X, Y | ||

| File | SAVE | Exports your program to example.bas. |

SAVE example.bas | ||

LOAD | Imports the example.bas program, replaces your current program. | |

LOAD example.bas | ||

| Screen | COLOR | Sets the interface RGB colors, see theme. |

COLOR $50f2, $b0f9, $a0f8 | ||

CLS | Clears the screen. | |

CLS | ||

DRAW | Sets position of drawing. | |

DRAW 100, 320 | ||

MODE | Sets drawing mode, see varvara. | |

MODE 04 | ||

POKE | Stores data into the font memory bank, the first value is an ascii byte value. | |

POKE 1, $1c1c, $087f, $0814, $2241 | ||

PICT | Draws a picture from a file, uses MODE. | |

PICT image10x10.icn PICT image12x18.chr |

Tic-Tac-Toe

Here's a complete example that uses everything above and implements a graphical tic-tac-toe game.

1 REM Create Assets: play[012] grid[567] 2 POKE 1, $c3e7, $7e3c, $3c7e, $e7c3 3 POKE 2, $187e, $7eff, $ff7e, $7e18 4 POKE 5, $1818, $1818, $1818, $1818 5 POKE 6, $0000, $00ff, $ff00, $0000 6 POKE 7, $1818, $3cff, $ff3c, $1818 7 REM Game Loop 8 GOSUB 160 9 GOSUB 120 10 IF W=0 GOTO 8 11 GOSUB 160 12 PRINT "WINNER: " #W 13 END 120 REM Request Player Turn 121 PRINT "Player " #P+1 " input position[0-8]:" 122 INPUT X 124 IF X>8 RETURN 130 REM Record Player Move 131 IF A.X GOTO 140 132 LET P:P=0, A.X:P+1 133 GOTO 150 140 REM Invalid Move 141 PRINT "This space is already taken! Input another one:" 142 GOTO 122 150 REM Validate board 151 IF A&B&C LET W:A 152 IF D&E&F LET W:D 153 IF G&H&I LET W:G 154 IF A&E&I LET W:A 155 IF G&E&C LET W:G 156 IF A&D&G LET W:A 157 IF B&E&H LET W:B 158 IF C&F&I LET W:C 159 RETURN 160 REM Draw Grid 161 CLS 162 PRINT #A #5 #B #5 #C 163 PRINT #6 #7 #6 #7 #6 164 PRINT #D #5 #E #5 #F 165 PRINT #6 #7 #6 #7 #6 166 PRINT #G #5 #H #5 #I 167 PRINT "" 168 RETURN

- View Source, Uxntal.

- Repository, Uxntal

- Download ROM, itchio

- TinyBASIC User Manual

- Forth & BASIC, side-by-side

- Original illustrations by Rekka Bellum.

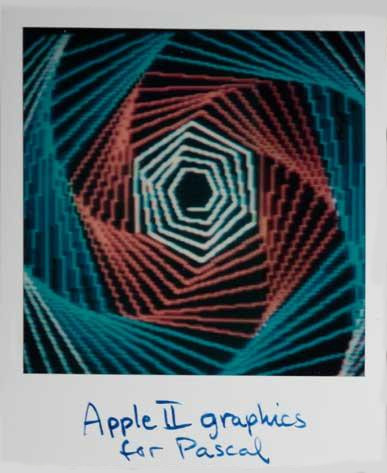

Pascal is an imperative and procedural programming language designed for teaching students structured programming.

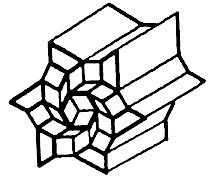

My main interest in the language is building little Macintosh applications such as graf3dscene, and exploring the THINK Pascal 4.0.2 environment. I have saved many example files in the Macintosh Cookbook repository.

THINK Pascal is a development system for the Macintosh, released by Think Technologies in 1986 as Lightspeed Pascal. Think Technologies was bought by Symantec, and the name was changed to Think Pascal. The last official update came 1992, and the product was officially discontinued in 1997.

Styleguide

A project should include the Runtime.lib library containing all standard Pascal routines such as writeln and sqrt. The interface.lib library contains the glue code for the all Macintosh Toolbox. Since routines from these two libraries are commonly used in almost all Pascal programs on the Macintosh, they are automatically included in the project file.

The standard adopted here concerns the naming of procedures, functions, and variables which both always start with an uppercase letter. Each new word within a name should also start with an uppercase letter. For example, GetNewWindow or SeekSpindle are fine function and procedure names; badPrcName isn't.

Variables always start with a lowercase letter. Use variable names like firstEmployee and currentTime. Global variables(variables accessible to your entire program) should start with a lowercase "g", like gCurrentWindow and gDone. The use of variable names such as glk and swpCk7 is discouraged.

program Example;

{Comment}

var

name: STRING;

begin

ShowText;

name := 'alice';

if (name = 'alice') then

Writeln('The name is alice.')

else if (a = 'bob') then

Writeln('The name is bob.')

else

Writeln('The name is not alice nor bob.');

end.

Creating a procedure

A procedure definition in Pascal consists of a header, local declarations and a body of the procedure. The procedure header consists of the keyword procedure and a name given to the procedure. A procedure does not return anything.

program ExampleProcedure; procedure DrawLine (x1, y1, x2, y2: INTEGER); begin Moveto(x1, y1); Lineto(x2, y2); end; begin ShowDrawing; DrawLine(20, 20, 100, 100); end.

Creating a function

A function declaration tells the compiler about a function's name, return type, and parameters. A function definition provides the actual body of the function.

program ExampleFunction;

function Add (a, b: INTEGER): INTEGER;

begin

add := a + b;

end;

begin

ShowText;

Writeln('5+6=', Add(5, 6));

end.

Creating a type

An Object is a special kind of record that contains fields like a record; however, unlike records, objects contain procedures and functions as part of the object. These procedures and functions are held as pointers to the methods associated with the object's type.

program ExampleType;

type

Rectangle = object

width, height: INTEGER;

end;

var

r1: Rectangle;

begin

ShowText;

New(r1);

r1.width := 12;

r1.height := 34;

Writeln('The rect is ', r1.width : 2, 'x', r1.height : 2);

end.

Creating a type with a method

program ExampleMethod;

type

Rectangle = object

width, height: INTEGER;

procedure setwidth (w: INTEGER);

end;

var

r1: Rectangle;

procedure Rectangle.setwidth (w: INTEGER);

begin

width := w;

end;

begin

ShowText;

New(r1);

r1.width := 12;

r1.height := 34;

Writeln('The rect was ', r1.width : 2, ' x ', r1.height : 2);

r1.setWidth(56);

Writeln('The rect is now ', r1.width : 2, ' x ', r1.height : 2);

end.

Creating a unit

To include the unit in another project, add uses ExampleUnit right after program Example, the procedures declared in the interface will become available.

unit ExampleUnit; interface procedure DrawLine (x1, y1, x2, y2: INTEGER); implementation procedure DrawLine (x1, y1, x2, y2: INTEGER); begin Moveto(x1, y1); Lineto(x2, y2); end; end.

Console Program

program ExampleConsole;

const

message = ' Welcome to the world of Pascal ';

type

name = STRING;

var

firstname, surname: name;

begin

ShowText;

Writeln('Please enter your first name: ');

Readln(firstname);

Writeln('Please enter your surname: ');

Readln(surname);

Writeln;

Writeln(message, ' ', firstname, ' ', surname);

end.

GUI Program

program ExampleGUI;

var

w: WindowPtr; {A window to draw in}

r: Rect; {The bounding box of the window}

begin

SetRect(r, 50, 50, 200, 100);

w := NewWindow(nil, r, '', true, plainDBox, WindowPtr(-1), false, 0);

SetPort(w);

MoveTo(5, 20);

DrawString('Hello world!');

while not Button do

begin

end;

end.

Graphics Primitives

Graphical user interface design rests firmly on the foundation of OOP and illustrates its power and elegance.

| Object | Pascal | Description |

| Pen | PenSize(width, height:INTEGER) | Sets the size of the plotting pen, in pixels |

| Pen- move absolute | MoveTo(h,v: INTEGER) | Moves pen (invisibly) to pixel (h,v) (absolute coordinates) |

| Pen- move relative | Move(dh,dv: INTEGER) | Moves pen (invisibly) dh pixels horizontally and dv pixels vertically (relative coordinates) |

| Point | DrawLine(x1,y1, x1,y1:INTEGER) | Draws a line from point (x1,y1) to the second point, (x1,y1), i.e. a point |

| Point | MoveTo(x1,y1: INTEGER) Procedure LineTo(x1,y1: INTEGER) |

Moves to pixel (x1,y1) and draws a line to (x1,y1), i.e. a point |

| Point | Line(dx,dy: INTEGER) | From the present position of the pen, draw a line a distance (0,0) |

| Line - absolute | DrawLine(x1,y1, x2,y2:INTEGER) | Draws a line from point (x1,y1) to the second point, (x2,y2) |

| Line - absolute | MoveTo(x1,y1: INTEGER) Procedure LineTo(x2,y2: INTEGER) |

Moves to pixel (x1,y1) and draws a line to (x2,y2) |

| Line - relative | Line(dx,dy: INTEGER) | Draw a line a distance (dx,dy) relative to the present pen position |

| Text | WriteDraw(p1) | The WriteLn equivalent procedure for the drawing window |

| Drawing Window | Procedure ShowDrawing | Opens the Drawing Window |

Graphic Primitives Example

program Primitives;

{Program to demonstrate Pascal point & line primitives.}

begin

ShowDrawing; {Opens Drawing Window}

{First draw three points by three different functions}

PenSize(1, 1); {Sets pen size to 1 x 1 pixels}

DrawLine(50, 50, 50, 50);

WriteDraw(' Point at (50,50) using DrawLine');

PenSize(2, 2);

MoveTo(100, 75); {Absolute move}

LineTo(100, 75);

WriteDraw(' Point at (100,75) using LineTo');

PenSize(3, 3);

MoveTo(150, 100); {Absolute move}

Line(0, 0);

WriteDraw(' Point at (150,100) using Line');

{Now Draw three lines by three different functions}

MoveTo(150, 175); {Absolute move}

WriteDraw('Line drawn with DrawLine');

DrawLine(150, 125, 50, 225);

PenSize(2, 2);

Move(0, 25); {Relative move}

LineTo(150, 250);

WriteDraw('Line drawn by LineTo');

Pensize(1, 1);

Move(0, 25); {Relative move}

Line(-100, 50);

WriteDraw('Line drawn by Line');

end.

Graphics Primitives - Geometric Figures

| Rectangles (Squares) |

Ovals (Circles) |

Rounded-Corner Rectangles |

Arcs and Wedges |

|

| Frame | ProcedureFrameRect(r:Rect) | ProcedureFrameOval(r:Rect) | Frame Round Rect (r:Rect; ovalWidth, ovalHeight:Integer) | FrameArc (r:Rect;startAngle, arcAngle:Integer) |

| Paint | PaintRect(r:Rect) | PaintOval(r:Rect) | Paint Round Rect(r:Rect; ovalWidth, ovalHeight:Integer) | PaintArc (r:Rect;startAngle, arcAngle:Integer) |

| Erase | EraseRect(r:Rect) | EraseOval(r:Rect) | Erase Round Rect(r:Rect; oval Width, ovalHeight:Integer) | EraseArc (r:Rect;startAngle, arcAngle:Integer) |

| Invert | InvertRect(r:Rect) | InvertOval(r:Rect) | Invert Round Rect(r:Rect; ovalWidth, ovalHeight:Integer) | InvertArc (r:Rect;startAngle, arcAngle:Integer) |

| Fill | FillRect(r:Rect, pat:Pattern) | FillOval(r:Rect,pat:Pattern) | FillRound Rect(r:Rect; ovalWidth, ovalHeight:Integer, pat:Pattern) | FillArc (r:Rect;startAngle, arcAngle:Integer, pat:Pattern) |

Spiral Pattern

program EulerSpiral; const l = 4; a = 11; var wx, wy, wa: real; i: INTEGER; procedure DrawLineAngle; var t: REAL; begin MoveTo(round(wx), round(wy)); t := wa * PI / 180; wx := wx + l * cos(t); wy := wy + l * sin(t); wa := wa + (i * a); LineTo(round(wx), round(wy)); end; begin wx := 100; wy := 300; i := 0; ShowDrawing; repeat DrawLineAngle; i := i + 1; until i > 20000; end.

Button Events

| Object | Pascal Syntax | Example Call | Description |

| Button | Function Button:Boolean | if Button then º elseº |

The Button function returns True if the mouse button is down; False otherwise |

| Button | Function StillDown: Boolean | if StillDown thenº elseº |

Returns True if the button is still down from the original press; False if it has been released or released and repressed (i.e., mouse event on event queue) |

| Button | Function WaitMouseUp:Boolean | if WaitMouseUp thenº elseº |

Same as StillDown, but removes previous mouse event from queue before returning False |

| Mouse cursor | GetMouse(var mouseLoc:Point) | GetMouse(p); | Returns the present mouse cursor position in local coordinates as a Point type |

| Pixel Value | Function GetPixel(h,v:point:Integer): Boolean | GetPixel(10,10); | Returns the pixel at position. |

| Keyboard | GetKeys(var theKeys:KeyMap) | GetKeys(key); | Reads the current state of the keyboard and returns a keyMap, a Packed Array[1..127] of Boolean |

| Clock | Function TickCount:LongInt | if TickCount<60 thenº | Returns the total amount of a 60th of a second since the computer was powered on. |

| Event | Function GetNextEvent (eventMask:Integer;var theEvent:EventRecord): Boolean |

if GetNextEvent(2,Rec) thenº elseº |

A logical function which returns True if an event of the requested type exists on the event queue; False otherwise. If True, it also returns a descriptive record of the event. (type, location, time, conditions, etc) |

Notes

A semi-colon is not required after the last statement of a block, adding one adds a "null statement" to the program, which is ignored by the compiler.

The programmer has the freedom to define other commonly used data types (e.g. byte, string, etc.) in terms of the predefined types using Pascal's type declaration facility, for example:

type byte = 0..255; signed_byte = -128..127; string = packed array[1..255] of char;

If you are using decimal (real type) numbers, you can specify the number of decimal places to show with an additional colon:

Writeln(52.234567:1:3);

The 'whole number' part of the real number is displayed as is, no matter whether it exceeds the first width (in this case 1) or not, but the decimal part is truncated to the number of decimal places specified in the second width. The previous example will result in 52.234 being written.

Patterns

The available patterns are:

- black

- dkgray

- gray

- ltgray

- white

The following Think Pascal commands will be useful to you in writing interactive graphics programs on the Macintosh. They are listed by type:

Window Commands

| ShowDrawing | Open the drawing window (if not already open) and make it the active window on the screen. Should be used when first draw to drawing window and anytime shift from text to drawing window. |

| ShowText | Similarly for the text window. |

| HideAll | Closes all Think Pascal windows on the screen. |

| SetDrawingRect(WindowRect) | Set Drawing Window to fit WindowRect |

| SetTextRect(WindowRect) | Set Text Window to fit WindowRect |

Writing words on the screen:

| Writeln('text') | Prints text to the Text Window and moves cursor to next line. |

| Writeln(INTEGER) | Prints INTEGER in the Text Window and moves cursor to next line. |

| Writeln(INTEGER : d ) | Prints INTEGER in the Text Window using at least d spaces and then moves cursor to next line. |

| Write('text') | Prints text to the Text Window but does not move cursor to next line. |

| WriteDraw('text') | Prints text to the Drawing Window, starting at the CP. The CP is left at the lower right corner of the last character drawn. |

Builtin Types

| Type | Records |

| Rect | left, top, right, bottom : INTEGER |

| Point | h, v : INTEGER |

Builtin Procedures

| SetPt(VAR pt : Point; h,v : INTEGER) | Make point, pt,with coords (h,v) |

| SetRect(VAR r : Rect; left, top, right, bottom : INTEGER) | Make rectangle with coords (left,top) and (right,bottom) as corners. |

| OffSetRect(VAR r : Rect; left, top : INTEGER) | Change rectangle to coords (left,top). |

| InSetRect(VAR r : Rect; right, bottom : INTEGER) | Change rectangle to coords (left,top). |

| Pt2Rect( pt1, pt2 : Point; dstRect : Rect); | Make rectangle with pt1 and pt2 as corners |

| PtInRect(pt:Point; r : Rect) : BOOLEAN; | Determine if pt is in the rectangle r. |

String Procedures

| NumToString(theNum: LongInt, theString: str255); | Converts a number to a string. |

| StringToNum(theString: str255, theNum: LongInt); | Converts a string to a number. |

| Concat(theString1, theString2, theString3, ..: string); | Combines strings. |

Bit Operations

| Band(n, i : longint) : boolean |

| Btst(n, i : longint) : boolean |

| Bxor(i, j : longint) : longint |

| Bor(n, i : longint) : longint |

| Bsl(n, i : longint) : longint |

| Bsr(n, i : longint) : longint |

Syntax

^Shapeis a type which is a pointer to the type ShapemyShape^takes a ^Shape and dereferences the pointer into a value@myShapetakes a Shape and captures its address, giving you a ^Shapevar myShapeShape is part of a argument declaration which means that the argument is passed as a reference, allowing the called procedure to modify it

Customization

If you are using THINK Pascal 4.0.2, as opposed to 4.5d4, the select all shortcut will be missing, and the default build shortcut will be ⌘G, instead of ⌘R. To change the menu shortcuts, open THINK Pascal with ResEdit, and add the missing shortcuts to the MENU resource. Remove the ⌘A shortcut from the Seach Again menu.

Going Further

The absolute best books on THINK Pascal are:

- Macintosh Pascal Programming Primer, Dave Mark & Cartwright Reed

- Programming in Macintosh and Think Pascal, Richard A. Rink & Vance B. Wisenbaker

- THINK Pascal: User Manual, Symantec. Inc

- Pascal Reference Manual, Apple Computer. Inc

C is the native language of Unix. It has come to dominate systems programming in the computer industry.

Work on the first official C standard began in 1983. The major functional additions to the language were settled by the end of 1986, at which point it became common for programmers to distinguish between "K&R C" and ANSI C.

People use C because it feels faster. If you build a catapult that can hurl a bathtub with someone inside from London to New York, it will feel very fast both on take-off and landing, and probably during the ride, too, while a comfortable seat in business class on a transatlantic airliner would probably take less time but you would not feel the speed nearly as much. ~

One good reason to learn C, even if your programming needs are satisfied by a higher-level language, is that it can help you learn to think at hardware-architecture level. For notes specific to the Plan9's C compiler, see Plan9 C.

Compile

To convert source to an executable binary one uses a compiler. My compiler of choice is tcc, but more generally gcc is what most toolchains will use on Linux.

cc -Wall -lm -o main main.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <math.h>

int count = 10;

int

add_together(int x, int y)

{

int result = x + y;

return result;

}

typedef struct {

int x;

int y;

int z;

} point;

void

print_point(point point)

{

printf("the point is: (%d,%d,%d)\n",point.x,point.y,point.z);

}

int

main(int argc, char** argv)

{

point p;

p.x = 2;

p.y = 3;

p.z = 4;

float length = sqrt(p.x * p.x + p.y * p.y);

printf("float: %.6f\n", length);

printf("int: %d\n", p.z);

print_point(p);

return 0;

}

Include

Generally, projects will include .h files which in turn will include their own .c files. The following form is used for system header files. It searches for a file named file in a standard list of system directories.

#include <file>

The following form is used for header files of your own program. It searches for a file named folder/file.h in the directory containing the current file.

#include "folder/file.h"

IO

One way to get input into a program or to display output from a program is to use standard input and standard output, respectively. The following two programs can be used with the unix pipe ./o | ./i

o.c

#include <stdio.h>

int

main()

{

printf("(output hello)");

return 0;

}

i.c

#include <stdio.h>

int

main()

{

char line[256];

if(fgets(line, 256, stdin) != NULL) {

printf("(input: %s)\n", line);

}

return 0;

}

Threads

Threads are a way that a program can spawn concurrent operations that can then be delegated by the operating system to multiple processing cores.

cc threads.c -o threads && ./threads

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#define NTHREADS 5

void

*myFun(void *x)

{

int tid;

tid = *((int *) x);

printf("Hi from thread %d!\n", tid);

return NULL;

}

int

main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

pthread_t threads[NTHREADS];

int thread_args[NTHREADS];

int rc, i;

/* spawn the threads */

for (i=0; i<NTHREADS; ++i)

{

thread_args[i] = i;

printf("spawning thread %d\n", i);

rc = pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL, myFun, (void *) &thread_args[i]);

}

/* wait for threads to finish */

for (i=0; i<NTHREADS; ++i) {

rc = pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);

}

return 1;

}

SDL

cc demo.c -I/usr/local/include -L/usr/local/lib -lSDL2 -o demo

To compile the following example, place a graphic.bmp file in the same location as the c file, or remove the image block.

#include <SDL2/SDL.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int

error(char* msg, const char* err)

{

printf("Error %s: %s\n", msg, err);

return 1;

}

int

main()

{

SDL_Window* window = NULL;

SDL_Surface* surface = NULL;

SDL_Surface* image = NULL;

if(SDL_Init(SDL_INIT_VIDEO) < 0)

return error("init", SDL_GetError());

window = SDL_CreateWindow("Blank Window",

SDL_WINDOWPOS_UNDEFINED,

SDL_WINDOWPOS_UNDEFINED,

640,

480,

SDL_WINDOW_SHOWN);

if(window == NULL)

return error("window", SDL_GetError());

surface = SDL_GetWindowSurface(window);

SDL_FillRect(surface, NULL,

SDL_MapRGB(surface->format, 0x72, 0xDE, 0xC2));

/* Display an image */

image = SDL_LoadBMP("graphic.bmp");

if(image == NULL)

return error("image", SDL_GetError());

SDL_BlitSurface(image, NULL, surface, NULL);

/* Draw canvas */

SDL_UpdateWindowSurface(window);

SDL_Delay(2000);

/* close */

SDL_FreeSurface(surface);

surface = NULL;

SDL_DestroyWindow(window);

window = NULL;

SDL_Quit();

return 0;

}

Misc

String padding: |Hello |

printf("|%-10s|", "Hello");

Macros

#define MIN(a, b) (((a) < (b)) ? (a) : (b)) #define MAX(a, b) (((a) > (b)) ? (a) : (b)) #define ABS(a) (((a) < 0) ? -(a) : (a)) #define CLAMP(x, low, high) (((x) > (high)) ? (high) : (((x) < (low)) ? (low) : (x)))

People use C because it feels faster. Like, if you build a catapult strong enough that it can hurl a bathtub with someone crouching inside it from London to New York, it will feel very fast both on take-off and landing, and probably during the ride, too, while a comfortable seat in business class on a transatlantic airliner would probably take less time but you would not feel the speed nearly as much.Erik Naggum

- Sigrid on C

- Aiju on C

- cproc, C11 compiler

Smalltalk is an object-oriented language and environment, created for educational use.

In a Workspace, you can evaluate a selection and get the result with mouse2, and print it:

"Comment between double-quotes." | x y sum | x _ 4. y _ 16rF. sum _ x + y. 19 "Strings are within single-quotes" |pokemon| pokemon _ 'Drifloon' Drifloon "To print the time" Time now 6:49:44 pm

If you'd like to know more about a specific class:

Pen inspect.

Smalltalk uses the left-arrow notation to assign, which is inserted with _, the vertical-arrow is inserted with ^.

Conditional

| x | x _ 15. ( x > 10) ifTrue: ['True'] ifFalse: ['False'].

Loops

Open a new window to show the System Transcript.

| x | x _ 1. 10 timesRepeat: [ Transcript show: (x\\3) printString; cr. x _ x + 1. ]

Drawing

Fill the screen

Display white Display gray Display black

FizzBuzz

| i fizz buzz | i _ 1. 100 timesRepeat: [ fizz _ i\\3=0. buzz _ i\\5=0. (fizz) ifTrue: [Transcript show: 'Fizz']. (buzz) ifTrue: [Transcript show: 'Buzz']. (fizz | buzz) ifFalse: [Transcript show: i printString]. Transcript cr. i _ i + 1. ]

Emulation

To change the resolution of the window of the Smalltalk-80 emulator:

DisplayScreen displayExtent: 800@480.

The emulator below uses alt+left click for mouse3.

Hypertalk is the programming language used in the mac software Hypercard.

Hypertalk can be emulated easily using a Macintosh emulator, the default Hypercard canvas size is 512x342.

For most basic operations including mathematical computations, HyperTalk favored natural-language ordering of predicates over the ordering used in mathematical notation. For example, in HyperTalk's put assignment command, the variable was placed at the end of the statement:

put 5 * 4 into theResult

Go

The go command can be used in two ways. It can allow the user to go to any card in the stack that it is in or to any card of any other stack that is available.

visual effect dissolve go to card id 3807

Put/Set

To change the text value, or textstyle of a field:

on mouseUp put random(100) into card field "target" set the textstyle of card field "Title" to italic end mouseUp

Alternative, one can use the "type" command if the programmer wants to simulate someone typing something into a field. The type command will do very well here:

on mouseUp select before first line of card field "target" type "hello there" end mouseUp

Show/Hide

The hide command can be used to hide any object. Some examples are: buttons, fields, and the menubar. The opposite of the hide command is the show command, and it can be used to make an object show up again.

-- a comment onmouseUp hide card field "title" wait 5 seconds show card field "title" endmouseUp

Choose

Each of the tools in the tool menu has a name that can be used with this command.

onmouseUp choose spray can tool set dragSpeed to 150 drag from 300,100 to 400, 200 wait 1 second choose eraser tool drag from 300,100 to 400, 200 choose browse tool endmouseUp

The available tools are:

- browse

- brush

- bucket

- button

- curve

- eraser

- field

- lasso

- line

- oval

- pencil

- rect[angle]

- reg[ular] poly[gon]

- round rect[angle]

- select

- spray

- text

Modal

Basic

on mouseUp ask "What is your name?" put it into response answer "You said " & response end mouseUp

Logic with input

on mouseUp

ask "What is your name?"

put it into response

if response is "blue" then

answer "correct."

else

answer "incorrect."

end if

end mouseUp

Logic with choices

on mouseUp

answer "Which color?" with "cyan" or "magenta" or "yellow"

if it is "cyan" then

answer "You selected cyan."

else

answer "You did not select cyan."

end if

end mouseUp

Play

The play command plays the specified sequence of notes with the specified sampled sounds. The tempo parameter specifies the number of quarter notes per minute; the default value is 120.

play "harpsichord" "c4 a3 f c4 a3 f c4 d c c c"

Globals

The global command is used to specify variables which will be available to other scripts within the stack or even in another stack. Unless variables are declared a global, they are considered by HyperTalk as local which means that they may only be used within a single script. If they are global, they may be carried to other scripts. Variables must be identified before they are used in order for them to become global.

-- allow access to globals global var1, var2, .. answer "hello " & var1 & "."

Summary

-- Let's put it altogether now

on mouseUp

put random of 100 into n

repeat 6

ask "please input number(1-100)?"

if it < n then

answer "more than" && it

else if it > n then

answer "less than" && it

else if it is n then

answer "perfect!"

exit mouseUp

end if

end repeat

answer "You lose, myy answer is " && n

end mouseUp